- Home

- John Jakes

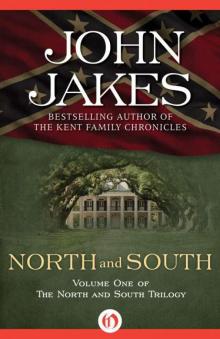

North and South Trilogy

North and South Trilogy Read online

The North and South Trilogy

John Jakes

CONTENTS

North and South

Prologue: Two Fortunes

Book One: Answer the Drum

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Book Two: Friends and Enemies

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Book Three: “The Cords That Bind Are Breaking One by One”

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Book Four: March Into Darkness

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Afterword

Love and War

Prologue: Ashes of April

Book One: A Vision From Scott

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Book Two: The Downward Road

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Book Three: A Worse Place Than Hell

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Book Four: “Let Us Die to Make Men Free”

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Book Five: The Butcher’s Bill

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Chapter 97

Chapter 98

Chapter 99

Chapter 100

Chapter 101

Chapter 102

Chapter 103

Chapter 104

Chapter 105

Chapter 106

Chapter 107

Chapter 108

Chapter 109

Chapter 110

Chapter 111

Chapter 112

Chapter 113

Chapter 114

Chapter 115

Chapter 116

Chapter 117

Chapter 118

Book Six: The Judgments of the Lord

Chapter 119

Chapter 120

Chapter 121

Chapter 122

Chapter 123

Chapter 124

Chapter 125

Chapter 126

Chapter 127

Chapter 128

Chapter 129

Chapter 130

Chapter 131

Chapter 132

Chapter 133

Chapter 134

Chapter 135

Chapter 136

Chapter 137

Chapter 138

Chapter 139

Chapter 140

Chapter 141

Chapter 142

Chapter 143

Chapter 144

Chapter 145

Chapter 146

Chapter 147

Afterword

Heaven and Hell

Prologue: The Grand Review, 1865

Book One: Lost Causes

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Book Two: A Winter Count

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Book Three: Banditti

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapt

er 37

Chapter 38

Book Four: The Year of the Locust

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Book Five: Washita

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Book Six: The Hanging Road

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Book Seven: Crossing Jordan

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Epilogue: The Plain, 1993

Afterword

A Biography of John Jakes

Copyright

North and South

The North and South Trilogy (Book One)

John Jakes

In memory of

Jonathan Daniels

Islander, Southerner, American, Friend

CONTENTS

Prologue: Two Fortunes

Book One: Answer the Drum

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Book Two: Friends and Enemies

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Book Three: “The Cords That Bind Are Breaking One by One”

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Book Four: March Into Darkness

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Afterword

Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness.

Psalm 88

Prologue:

Two Fortunes

1686: The Charcoal Burner’s Boy

“THE LAD SHOULD TAKE my name,” Windom said after supper. “It’s long past time.”

It was a sore point with him, one he usually raised when he’d been drinking. By the small fire, the boy’s mother closed the Bible on her knees.

Bess Windom had been reading to herself as she did every evening. From watching her lips move, the boy could observe her slow progress. When Windom blurted his remark, Bess had been savoring her favorite verse in the fifth chapter of Matthew: “Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

The boy, Joseph Moffat, sat with his back against a corner of the chimney, whittling a little boat. He was twelve, with his mother’s stocky build, broad shoulders, light brown hair, and eyes so pale blue they seemed colorless sometimes.

Windom gave his stepson a sullen look. A spring rain beat on the thatch roof. Beneath Windom’s eyes, smudges of charcoal dust showed. Nor had he gotten the dust from under his broken nails. He was an oafish failure, forty now. When he wasn’t drunk, he cut wood and smoldered it in twenty-foot-high piles for two weeks, making charcoal for the small furnaces along the river. It was dirty, degrading work; mothers in the neighborhood controlled their errant youngsters with warnings that the charcoal man would get them.

Joseph said nothing, just stared. Windom didn’t miss the tap-tap of the boy’s index finger on the handle of his knife. The boy had a high temper. Sometimes Windom was terrified of him. Not just now, though. Joseph’s silence, a familiar form of defiance, enraged the stepfather.

Finally Joseph spoke. “I like my own name.” He returned his gaze to his half-carved coracle.

“By God, you cheeky whelp,” Windom cried in a raspy voice, overturning his stool as he lunged toward the youngster.

Bess jumped between them. “Let him be, Thad. No true disciple of our Savior would harm a child.”

“Who wants to harm who? Look at him!”

Joseph was on his feet and backed against the chimney. The boy’s chest rose and fell fast. Unblinking, he held the knife at waist level, ready to slash upward.

Slowly Windom opened his fist, moved away awkwardly, and righted his stool. As always, when fear and resentment of the boy gripped him, it was Bess who suffered. Joseph resumed his seat by the fire, wondering how much longer he could let it go on.

“I’m sick of hearing about your blessed Lord,” Windom told his wife. “You’re always saying He’s going to exalt the poor man. Your first husband was a fool to die for that kind of shit. When your dear Jesus shows up to dirty His hands helping me with the charc, then I’ll believe in Him, but not before.”

He reached down for the green bottle of gin.

Later that night, Joseph lay tense on his pallet by the wall, listening to Windom abuse his mother with words and fists behind the ragged curtain that concealed their bed. Bess sobbed for a while, and the boy dug his nails into his palms. Presently Bess made different sounds, moans and guttural exclamations. The quarrel had been patched up in typical fashion, the boy thought cynically.

He didn’t blame his poor mother for wanting a little peace and security and love. She’d chosen the wrong man, that was all. Long after the hidden bed stopped squeaking, Joseph lay awake, thinking of killing the charcoal burner.

He would never take his stepfather’s name. He could be a better man than Windom. His defiance was his way of expressing faith in the possibility of a better life for himself. A life more like that of Andrew Archer, the ironmaster to whom Windom had apprenticed him two years ago.

Sometimes, though, Joseph was seized by dour moods in which he saw his hopes, his faith, as so much foolish daydreaming. What was he but dirt? Dirty of body, dirty of spirit. His clothes were never free of the charcoal dust Windom brought home. And though he didn’t understand the crime for which his father had suffered and died in Scotland, he knew it was real, and it tainted him.

“Blessed are they which are persecuted …” No wonder it was her favorite verse.

Joseph’s father, a long-jawed, unsmiling farmer whom he remembered only dimly, had been an unyielding Covenanter. He had bled to death after many app

lications of the thumbscrew and the boot, in what Bess called the killing time: the first months of the royal governorship of the Duke of York, the same man who had lately been crowned James II. The duke had sworn to root out the Presbyterians and establish episcopacy in the country long troubled by the quarrels of the deeply committed religious and political antagonists.

Friends had rushed to Robert Moffat’s farm to report the owner’s gory death in custody and to warn his wife to flee. This she did, with her only son, barely an hour before the arrival of the duke’s men, who burned all the buildings on the property. After months of wandering, mother and son reached the hills of south Shropshire. There, as much from weariness as anything else, Bess decided to stop her running.

The wooded uplands south and west of the meandering Severn River seemed suitably rustic and safe. She rented a cottage with the last of the money she had carried out of Scotland. She took menial jobs and in a couple of years met and married Windom. She even pretended to have adopted the official faith, for although Robert Moffat had infused his wife with religious fervor, he hadn’t infused her with the courage to continue to resist the authorities after his death. Her faith became one of resignation in the face of misery.

A spineless and worthless faith, the boy soon concluded. He would have none of it. The man he wanted to imitate was strong-minded Archer, who lived in a fine mansion on the hillside above the river and the furnace he owned.

Hadn’t old Giles told Joseph that he had the wits and the will to achieve that kind of success? Hadn’t he said it often lately?

Joseph believed Giles much of the time. He believed him until he looked at the charcoal dust under his own nails and listened to the other apprentices mocking him with cries of “Dirty Joe, black as an African.”

Then he would see his dreams as pretense and laugh at his own stupidity until his pale eyes filled with shameful but unstoppable tears.

Old Giles Hazard, a bachelor, was one of the three most important men at the Archer ironworks. He was in charge of the finery, the charcoal forge in which cast-iron pigs from the furnace were re-melted to drive off an excess of carbon and other elements which made cast iron too brittle for products such as horseshoes, wheel rims, and plow points. Giles Hazard had a gruff voice and a bent for working his men and apprentices like slaves. He had lived within a ten-minute walk of the furnace all his life and had gone to work there at age nine.

He was a short, portly fellow, possessed of immense energy despite his weight. Physically, he might have been a much older version of Joseph. Perhaps that was one reason he treated the boy almost like a son.

Another reason was that Joseph learned quickly. Joseph had come to Giles’s attention last summer, about the time he was beginning his second year at Archer’s. Giles had been discussing the apprentices with the man in charge of the furnace. The man had bragged about how nimbly Joseph worked his way around the sand trough, where bright molten iron flowed out to many smaller, secondary troughs that resembled piglets suckling on the mother sow. The look of the main and secondary troughs had long ago led to the name “pig iron” for the finished castings.

The Bastard

The Bastard The Furies

The Furies The Bold Frontier

The Bold Frontier The Americans

The Americans Mention My Name in Atlantis

Mention My Name in Atlantis California Gold

California Gold North and South

North and South Savannah, or a Gift for Mr. Lincoln

Savannah, or a Gift for Mr. Lincoln Heaven and Hell

Heaven and Hell Homeland

Homeland On Secret Service

On Secret Service The Lawless

The Lawless The Titans

The Titans The Seekers

The Seekers Love and War

Love and War North and South: The North and South Trilogy (Book One)

North and South: The North and South Trilogy (Book One) North and South Trilogy

North and South Trilogy Love and War: The North and South Trilogy

Love and War: The North and South Trilogy North and South: The North and South Trilogy

North and South: The North and South Trilogy Savannah

Savannah Lawless

Lawless Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes

Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes Love and War: The North and South Trilogy (Book Two)

Love and War: The North and South Trilogy (Book Two) The Rebels: The Kent Family Chronicles

The Rebels: The Kent Family Chronicles Heaven and Hell: The North and South Trilogy

Heaven and Hell: The North and South Trilogy Planet of the Apes Omnibus 2

Planet of the Apes Omnibus 2 The Bastard: The Kent Family Chronicles

The Bastard: The Kent Family Chronicles Heaven and Hell: The North and South Trilogy (Book Three)

Heaven and Hell: The North and South Trilogy (Book Three)